If you remember to begin the process of product development with the customer, you will not be afraid of the competitive, accelerated market because you will be standing on a strong foundation.

Customers Don’t Need Startups

The saying, “It’s a start-up!” reflects a perception of product mass production as if it were designed for a single audience. This view of management promotes the myth of the “genius entrepreneur” who can, with a single stroke, bring up a winning idea that changes customers’ consumer behavior, or, alternatively, the entrepreneur who designs customer’s behavior (through marketing manipulations). This business practice is rapidly becoming irrelevant.

Development of a product according to Lean Product & Process Development (LPPD) methodology does not begin with a technological flash of genius, but rather from an understanding of the customer and an answer to this question: What does the customer need? After all, this is the purpose of the development. The concept of “need” is elusive, since the customer’s needs are multi-dimensional and bound to time and context. Yet, in any case, the entrepreneur’s purpose shouldn’t be merely strive to “exit” and “get rich” since there isn’t a customer in the world who would be interested in making an entrepreneur who doesn’t respond to his real need rich. A response to the needs of the customer is a sequence of solutions to different customers at given, defined times, and the influences of this process flows in two directions: The customer is a partner in the design of the product and the quality of the initiative.

A product’s successful entry into the market is the result of a process of trial and error performed by an entrepreneur-tailor. The development of an idea in secrecy, without including the customer could turn out to be a waste, creating yet another product that only aggressive marketing can be brought into the market only through aggressive marketing.

In a competitive market, presentation of early Time to Market (TTM) is critical, since the speed in which an idea can be translated into a proven potential solution determines the status of the entrepreneur in the market, and any delay could cause him to miss out on being the first. But even from this point of view, practical testing of an idea (hypothesis) in the field through presentation of an initial model (the Minimum Viable Product – MVP) is preferable, since it lowers the level of risk of developing an unsuitable product and great loss of time.

Customers Can Be Innovative, Too

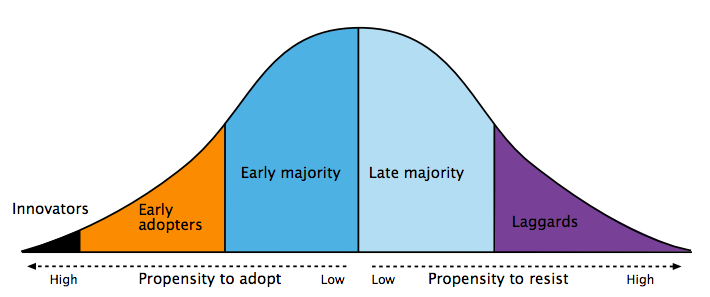

The process described above requires contact with different sorts of customers. The customer is not only characterized in a certain way, but also according to his willingness to experiment – that is, in the extent of his innovation and daring as a customer.

The ability to penetrate the market with a new product begins with successful location of the group of customers defined as “innovators” (who compose up to 3% of the market); these are the customers who have higher discretionary income and curiosity that propels them to try (and even to take a risk) as a solution to an emotional (adventure and change) or social (being first and influencing the development of a product) need. The ability to identify and build preliminary collaboration with a group of innovative customers is a necessary condition for the success of the efforts of development.

The ability to penetrate the market with a new product begins with successful location of the group of customers defined as “innovators” (who compose up to 3% of the market); these are the customers who have higher discretionary income and curiosity that propels them to try (and even to take a risk) as a solution to an emotional (adventure and change) or social (being first and influencing the development of a product) need. The ability to identify and build preliminary collaboration with a group of innovative customers is a necessary condition for the success of the efforts of development.

Continued development is dependent on expansion of the circles of users. The “Early Adopters” (up to 14% of the market) includes customers who also want to be innovative, but not at any price and want innovation without risk. The Early Adopters will not be the first to purchase the produce, but they will be willing to absorb instability and set-backs in exchange for a value package that could potentially meet their needs.

The continued development of the produce requires penetration into the heart of the market, the “Early and Late Majorities,” who expect a mature, stable, and low-cost product that will change the nature of the market. Expansion of the circle of users pulls in additional actors when the competition is focused on improvement of quality, level of service, and price-cutting. Tesla, the new electronic car produced by Elon Musk is an example of an attractive product that caught the attention of the innovators and some of the early adopters, but is still finding it difficult to penetrate into the heart of the market with a mature product at an attractive price.

From Innovative Adventure to a Price Competitive, Reliable Product

Therefore, each type of customer has his own demands and needs, and the product must be adapted to the customers during the various stages of development. The attempt to produce a fully completed (mature) product at the beginning of the development process could delay entry into the market (ITM) and thus it is preferable to build a “bridge head” together with the innovator customers; similarly, setting a high price for a product that is still struggling with various problems of quality (and is suited to the Innovators or Early Adopters) for the majority customers will threaten the competitive status of whoever penetrated the market first.

In today’s market, a traditional linear (“waterfall”) process of development that continues for years without engaging the customer will be less effective than an interactive process composed of a series of launches of models of the produce (MVP, Alfa, Beta), such that each version replaces the previous version in a rapid series of design, study & research, development, and production.

Thus, across the development of the product, the models coalesce and become more mature in a manner suited to the openings of the circles of customers. In this context, three variables must be considered: 1) the timing of the entry into the market (ITM); 2) quality and maturity; 3) cost and price. Focusing on only one of these across the life of a product (such as insisting on the completion of the perfect product that prevents engaging innovative customers on the one hand; or, on the other hand, too-high a price at the stage of broad escalation and distribution) could diminish the entrepreneur’s ability to reach a maximum number of customers.

Google, Amazon, and Ikea are examples of companies that produce versions of a product and application on a continuous, daily level, alongside their long-term development. In order to maintain the continuity, they established integrated development teams who adapt themselves to the different stages in the process of development. A company that wishes to learn from global success must adopt a hybridized organization culture (in the manner that GE did), which combines the innovation and swiftness of a startup during the initial changes in the life of the product development with the maturity and reliability of an established company at the later stages.

Boaz Tamir,

ILE.

Leave a Reply